|

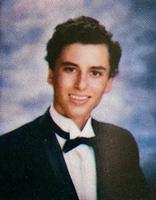

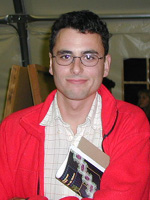

Feb 4, 1976 - Mar 5, 2003

Eran Karmon took his own life at age 27 on March 5, 2003. He was an adventurous mountaineer and naturalist, accomplished biophysicist, professional science writer, and self-described "tough Jew". Though he lived and worked in Berkeley, California from 1998 until his death in March 2003, Karmon had traveled the world, climibing mountains mountains from Nepal to New Zealand and charming locals from Be'er Sheva to Budapest.

In addition to his love of travel, he was a formidable intellectual: a mathematician and Fulbright scholar— bookish but not the least bit nebbishy— with a love of particle physics, western non-fiction, and little-known installation art. Like many scientists on the Berkeley campus, he had a strong tie to socially relevant research.

Award-Winning Science Writer, Student Mourned

The Daily Californian

by Amelia Heagerty, Contribution Writer

Friday, March 21, 2003

A UC Berkeley graduate student was found dead in his apartment March 5 in an apparent suicide.

Eran Karmon was found hanging from a doorframe by a housemate.

Those who knew Karmon described him as eccentric, enthusiastic, colorful and funny. Friends and family are at a loss as to why the 27-year-old biophysics doctoral candidate took his own life

Karmon was an aspiring science writer who taught English in Nepal, climbed Mount Denali several times, founded the Berkeley Science Review, worked on an AIDS vaccine and possessed an "amazingly kooky" sense of humor.

"He took his humor seriously," said Leor Weinberger, a fellow biophysics graduate student who worked with Karmon on an AIDS vaccine. "He started the Militant Pedestrian Group, and he would just step out in front of cars because he was pissed off that they wouldn't let him cross."

Karmon received the Fulbright Fellowship and a Barry M. Goldwater scholarship. Last summer, he won the Seattle Times' American Association of the Advancement of Science fellowship for science writers.

"What struck me was his talent and his approach to life and to doing what he wanted to do, which was becoming a journalist and writing about science," said David Perlman, a longtime science writer for the San Francisco Chronicle. "Having counseled scores of young people over the years, I thought this guy was the most talented, promising and purposeful young man I had ever encountered."

Karmon was devoted to his fledgling publication, the Berkeley Science Review, and acted as its editor as well as founder.

Karmon played the banjo, ice-climbed, loved country music and once talked himself across the Chinese border without a visa.

"I think he was always looking for new things to do, and often in unconventional ways," said Seattle Times staff reporter Eric Sorensen. "He had this all-inclusive taste-he liked quantum mechanics, and he liked Seinfeld."

Karmon wrote an opinion piece in The Daily Californian on Jan. 16, 2001, after he found the back pain care at the Tang Center unsatisfactory.

"I think I may not be following all the instructions correctly, because my back still hurts. I have tried to 'diaper the baby while sitting next to him on the bed.' Almost religiously I have followed the command to 'never lift or move heavy furniture' ... But the pain continues. Who knows, maybe I have Bubonic Plague, or Punch card Insertion Syndrome."

Karmon is survived by his parents Dan and Judy Karmon, his brother Michael, and his sisters Galit and Adina.

____________________________________________________

By Eric Sorensen

Seattle Times staff reporter

On the Web:nature.berkeley.edu/~ekarmon/

BERKELEY, Calif. — Some possible requirements for those who would benefit from the fledgling Eran Karmon Memorial Fund:

A demonstrated ability to talk your way into China, without a visa, by chatting with a border guard in Nepali.

A résumé that includes at least a Fulbright Fellowship, a Barry M. Goldwater scholarship, an American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) media fellowship or equivalent.

A clear disgust with the fact that the global reach of Coca-Cola exceeds that of high-quality education and health care.

And if it isn't asking too much, could you try to cure AIDS?

Such is the burden of anyone who would emulate Mr. Karmon, a doctoral candidate in biophysics and a vastly talented science writer who was The Seattle Times' inaugural AAAS science-writing fellow last summer.

His family is contemplating a fund, possibly for a scholarship or a cause he believed in, after Mr. Karmon committed suicide March 5 in Berkeley, Calif. He was 27.

Mr. Karmon was a study in brilliance, youthful restlessness, relentless accomplishment and global interests. He would lie awake at night marveling at the beauty of quantum mechanics, but he also marveled at the recurring references on "Seinfeld" to Cosmo Kramer's never-seen friend, Bob Sacamano.

His expertise stretched from physics to geology to mathematical epidemiology, and his general-science knowledge was encyclopedic, but his rabbi thought he was a graduate student in music.

He was a bit nerdy, tall and slight of frame, staring at his shoes when he shook your hand and looking pencil-necked in a blazer, but he scaled 800-foot rock faces and trekked across glaciers around the world.

He was a person of extremes, said Greg Hura, a fellow graduate student in biophysics at the University of California, Berkeley.

"If you talked about Alaska, he immediately wanted to talk about Denali," Hura said the other day when some 40 friends and associates of Mr. Karmon met over pizza and pop to share their memories of him.

On top of the usual workload of graduate school, Mr. Karmon launched the Berkeley Science Review, a magazine of research by Berkeley graduate students.

"He wasn't afraid of barriers," said Leor Weinberger, another biophysics graduate student who was modeling the AIDS virus with Mr. Karmon. "He would break barriers as a rule sometimes."

And he took his humor very seriously. When a colleague pointed out that mints in a tin would be touched over and over as people dipped their fingers in it, he created a "virtual candy dish" and concluded the last piece of 300 mints would have been touched 4½ times. He posted a chart and his formula atnature.berkeley.edu/~ekarmon/virtual_candy_dish

"He was such a serious guy but always in a way that made you smile, you know? And lord, could he write," said Jacqui Banaszynski, a Seattle Times assistant managing editor.

"He was the most talented and promising young man I've ever seen," said the San Francisco Chronicle's David Perlman, dean of American science writing and, at 84, the self-described "oldest living science writer in the world."

Mr. Karmon had the fundamental gift of science writing, the ability to eloquently translate a world of arcane wonder and mystery, from the nature of fear to songbirds in the mood.

Here he is in the Seattle office of a would-be space pioneer:

"As offices go, Brad Edwards' isn't much to look at: a few chairs, a desk, a laptop, a cellphone and a bundle of decorative reeds. Not exactly mission control. But as traffic puffs along outside his window on Third Avenue in downtown Seattle, Edwards dreams of changing the future of space exploration.

"He wants to build a 62,000-mile elevator into space, and as far-fetched as that sounds, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) has given him $570,000 to research the possibilities."

In Edwards, Mr. Karmon had found a fellow dreamer, which may be the best criterion for beneficiaries of the Eran Karmon Memorial Fund.

He was buried March 7 in Simi Valley, Calif. He is survived by his parents, Dan and Judy Karmon; a brother, Michael of St. Paul, Minn.; and two sisters, Galit of Los Angeles, and Adina of Santa Cruz, Calif.

Donations to the Eran Karmon Memorial Fund can be sent to the Karmon family, 2252 N. Villa Maria Road, Claremont, CA 91711.

.jpg)

Mount Sinai Memorial Park - Simi Valley, California

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/163419237/eran-karmon#add-to-vc .png)

|